The Science Behind Warmer, Drier, Healthier Homes

Are Passive House certified homes set to be the next big thing in New Zealand? We talk to architect Joe Lyth about why Respond Architects is right behind the Passive House movement.

“Passive House is a rigorous, internationally recognised standard for energy efficient buildings,” explains Joe. “Using quality products, careful planning and attention to detail, you design and build a property that has a high performance envelope – both extremely airtight and insulated as the local climate requires. It’s warm, quiet, and best of all your power bills will be tiny. A certified Passive House uses no more than 15kW per square metre, per year to heat – that’s over 80% less energy than a typical family home in Auckland.”

So why aren’t more New Zealanders building Passive House certified homes? As Joe says, it’s a standard that’s relatively new in this country.

“The first Passive House was built in Germany back in 1990, while New Zealand’s first was built in 2012 – so we’re just starting to catch up here. Our Building Code standards around insulation, airtightness, ventilation, heat loss and energy efficiency are currently quite poor, with no mandatory airtightness requirements at all.”

The fact is that kiwis are used to living in cold, damp, draughty houses. One Danish builder observed that New Zealanders ‘don’t find it strange to wear coats and outdoor clothing when indoors’! The consequences of this, however, are serious. Studies show that the average New Zealand home is 16 degrees inside during winter, with the average bedroom temperature reaching just 13 degrees between midnight and 9am. This is far lower than the World Health Organisation standard of 18 degrees (or 20 degrees if babies or elderly live in the house)*. Cold homes are typically damp homes, which can lead to mould as well as a raft of illnesses. In fact, one in six New Zealanders are sick with respiratory illnesses, which costs $6.16 billion a year in public and private costs*.

Thankfully, the thinking is changing. Passive House benefits are becoming more widely known, and more certified Passive Houses are being built around the country. Banks are starting to recognise it too, with ANZ one of the first to offer lower mortgage rates if you build a certified Passive House. As a result, more builders and designers are getting the required registration to create these buildings – including Respond Architects, who Joe says is right behind the Passive House movement.

“Respond is currently working with Öko Konstrukt, specialists in the construction of high quality certified Passive Houses, to design Passive Houses in the new Weiti Bay development, north of Auckland. Co-owner Murray Durbin worked on the first Passive House in New Zealand, then went on to build his own Certified Passive House Plus, which carried a 10 Homestar built rating. Murray also imports and distributes European products and systems to help others meet this standard through his business ‘Enveloped’. We’re really excited to be working on the Weiti Bay development with him, and hope to see the relationship continue.”

Achieving Passive House certification

Airtightness is a key feature of a Passive House building, but it doesn’t mean you can’t open any windows. Instead, it’s about managing the amount of air leaking through the building fabric.

“The idea of ‘allowing a building to breathe’ isn’t actually a good thing,” says Joe. “Air carries heat and moisture with it into the building fabric, which can lead to mould and other issues. You need to stop air from entering the construction, while letting out any moisture that has come in. The interior air quality is kept fresh and clean through balanced heat recovery mechanical air ventilation systems, while excellent insulation, high performance window glazing and quality joinery ensure heat doesn’t escape.”

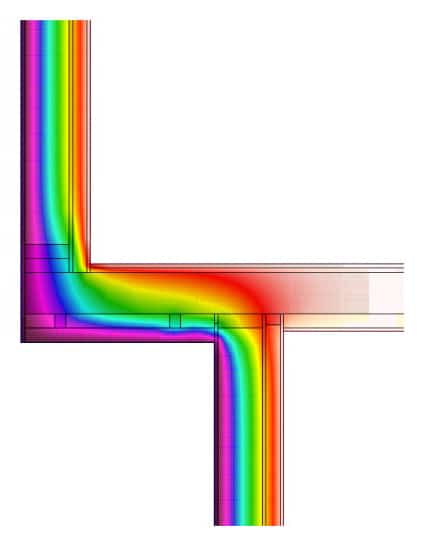

Passive House buildings also reduce thermal bridging as much as possible. As Joe explains, every material has a heat transmission value: with steel transferring more heat that timber, timber more than insulation. A thermal bridge is where a material with a higher heat transmission capacity bridges the thermal envelope of a house.

“Apart from heat loss, it can lead to condensation and even mould. Passive House design eliminates as many of these heat loss points as possible. It’s also about using the right products – high quality insulation for example, installed properly so there are no spaces through which heat can escape.”

Achieving Passive House certification requires rigorous on-site testing throughout the build process. ‘Blower door testing’ is used, where all windows and doors are closed and a fan is put on the front door to pressurise and depressurise the house. The amount of air loss or gain is measured and if it doesn’t meet the required levels, the design or materials need to be adjusted until it’s just right.

Heat loss is then balanced by taking into account the heat generated within the house – from the body heat of occupants, cooking appliances, the hot water system and sunlight.

“You look at what direction the house is facing and how much sun gets into each area throughout the day, through all seasons. You can even account for things like house plants – how much oxygen they give off and how much moisture they require. All of this information is plugged into a scientifically calculated spreadsheet called PHPP (Passive House Planning Package) and it tells you what capacity heating system you need to keep the home at 20 degrees Celsius, and whether you’ll need additional shading or active cooling during the hotter months. The formula is location specific, so in hotter climates it’s about how to cool the home to keep it at a pleasant temperature.”

A Passive House of his own

One key issue Respond hopes to address is cost. New Zealand is one of the most expensive countries in the world in which to build, and the cost of construction in the main centres rose more than 30 per cent over the past 10 years**. So, how are people expected to afford a premium on top of this to build to Passive Certification?

Joe says there’s no easy solution, but it’s something he’s currently trying to resolve as he designs a Passive House certified home for his family. He hopes to find a route through which Passive House certified homes can be produced within tighter budgets, using simple, functional interiors which can then be upgraded by the inhabitants over time, as their bank accounts allow.

“When you’re listening to your kids coughing in a cold, damp house every winter despite high heating bills, you realise there’s nothing more important than improving their quality of life. A warm, healthy envelope is the important bit, the rest can come later!

“Our goal is to show that designing a Passive House certified home isn’t as restrictive as you might think. While costs are currently higher than standard construction, you’ll save in power bills over the long run. Plus, the more Passive Houses that are built, the more the prices will come down and the more attainable having a warm, healthy home will become for New Zealanders.”

*Jason Quinn, Passive House for New Zealand – The warm healthy homes we need, 2019

**Chris Hutching, Is it really more expensive to build new in New Zealand?, stuff.co.nz article August 2019